Week 6

Race, Ethnicity and Nation

SOCI 269

Module II Begins–

March 4th

Reminder

Coding Assignment Deadline

Your coding assignments are due next week—i.e., by 8:00 PM on Monday, March 10th.

Reminder

Let’s Talk Boundaries

What Are “Boundaries?”

In recent years, the idea of “boundaries” has come to play a key role in important new lines of scholarship across the social sciences. It has been associated with research on cognition, social and collective identity, commensuration, census categories, cultural capital, cultural membership, racial and ethnic group positioning, hegemonic masculinity, professional jurisdictions, scientific controversies, group rights, immigration, and contentious politics, to mention only some of the most visible examples.

(Lamont and Molnár 2002:167, EMPHASIS ADDED)

What Are “Boundaries?”

Great! But what are boundaries?

What Are “Boundaries?”

Any takes?

What Are “Boundaries?”

Symbolic Boundaries

Symbolic boundaries are conceptual distinctions made by social actors to categorize objects, people, practices, and even time and space. They are tools by which individuals and groups struggle over and come to agree upon definitions of reality. Examining them allows us to capture the dynamic dimensions of social relations, as groups compete in the production, diffusion, and institutionalization of alternative systems and principles of classifications. Symbolic boundaries also separate people into groups and generate feelings of similarity and group membership … They are an essential medium through which people acquire status and monopolize resources.

(Lamont and Molnár 2002:168, EMPHASIS ADDED)

What Are “Boundaries?”

Social Boundaries

Social boundaries are objectified forms of social differences manifested in unequal access to and unequal distribution of resources (material and nonmaterial) and social opportunities. They are also revealed in stable behavioral patterns of association, as manifested in connubiality and commensality. Only when symbolic boundaries are widely agreed upon can they take on a constraining character and pattern social interaction in important ways. Moreover, only then can they become social boundaries, i.e., translate, for instance, into identifiable patterns of social exclusion or class and racial segregation.

(Lamont and Molnár 2002:168–69, EMPHASIS ADDED)

What Are “Boundaries?”

[S]ymbolic and social boundaries should be viewed as equally real: The former exist at the intersubjective level whereas the latter manifest themselves as groupings of individuals. At the causal level, symbolic boundaries can be thought of as a necessary but insufficient condition for the existence of social boundaries.

(Lamont and Molnár 2002:169, EMPHASIS ADDED)

What Are “Boundaries?”

Consider the process of collective identification.

What Are “Boundaries?”

Although collective identity formation is commonly conceptualized as a self-referential process, it usually also involves self-conscious efforts by members of a group to distinguish themselves from whom they are not, and hence it is better understood as a dialectical process whose key feature is the delineation of boundaries between “us” and “not us.”

(Zolberg and Woon 1999:8, EMPHASIS ADDED)

What Are “Boundaries?”

An Example

For a relevant paper, see Kuran (1998).

Boundary-Making

Boundaries in Flux

Crucially, boundaries are mutable and dynamic. Moreover, the distribution of people on either side of a boundary is not set in stone

(see Abascal 2020).

Boundaries in Flux

But how do these evolutionary shifts take root?

Let’s consider Zolberg and Woon’s (1999)

influential typology.

Boundaries in Flux

There are three basic strategies that individuals and social groups can pursue to navigate—and perhaps remake—the social and symbolic boundaries that pervade greater society.

Boundary Crossing

Boundary Blurring

Boundary Shifting

Boundaries in Flux

Individual boundary crossing … (occurs) without any change in the structure of the receiving society and leaving the distinction between insiders and outsiders unaffected. This is the commonplace process whereby immigrants change themselves by acquiring some of the attributes of the host identity. Examples include replacing their mother tongue with the host language, naturalization, and religious conversion.

(Zolberg and Woon 1999:8, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Boundary blurring … (is) based on a broader definition of integration—one that affects the structure (i.e., the legal, social, and cultural boundaries) of the receiving society. Its core feature is the tolerance of multiple memberships and an overlapping of collective identities hitherto thought to be separate and mutually exclusive; it is the taming or domestication of what was once seen as “alien” differences. Examples include formal or informal public bilingualism, the possibility of dual nationality, and the institutionalization of immigrant faiths (including public recognition, where relevant).

(Zolberg and Woon 1999:8–9, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Boundary shifting … denotes a reconstruction of a group’s identity, whereby the line differentiating members from nonmembers is relocated, either in the direction of inclusion or exclusion. This is a more comprehensive process, which brings about a more fundamental redefinition of the situation. By and large, the rhetoric of pro-immigration activists and of immigrants themselves can be read as arguments on behalf of the expansion of boundaries to encompass newcomers, while that of the anti-immigrant groups can be read as an attempt to redefine them restrictively in order to exclude them.

(Zolberg and Woon 1999:9, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Boundary Crossing

Boundary Blurring

Boundary Shifting: Contraction

Boundary Shifting: Expansion

Contraction & Group Threat–by Maria Abascal

Latino Ambiguity

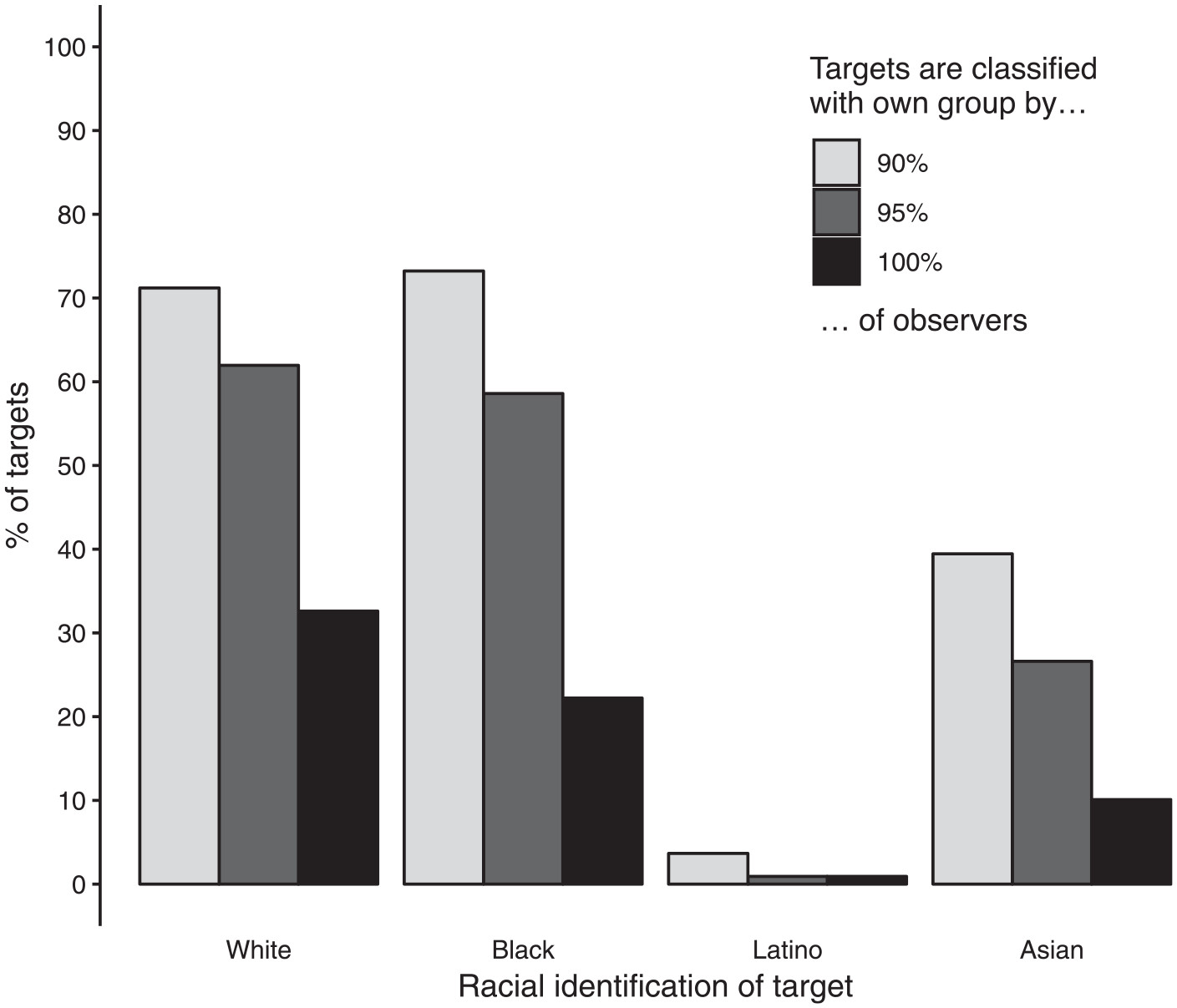

[S]elf-identified Latinos, who are themselves heterogeneous in terms of ancestry and phenotype, are probably the primary source of racial ambiguity in the United States today. A look at a racially diverse face database makes the point. The Chicago Face Database (CFD) … is a publicly available database of nearly 600 people who self-identify as White, Black, Latino, or Asian …[C]oncordance between self- and other-classification is lowest for self-identified Latinos. Concordance is highest for self-identified Whites and self-identified Blacks.

(Abascal 2020:304, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Latino Ambiguity

Figure 1 from Abascal (2020).

Latino Ambiguity

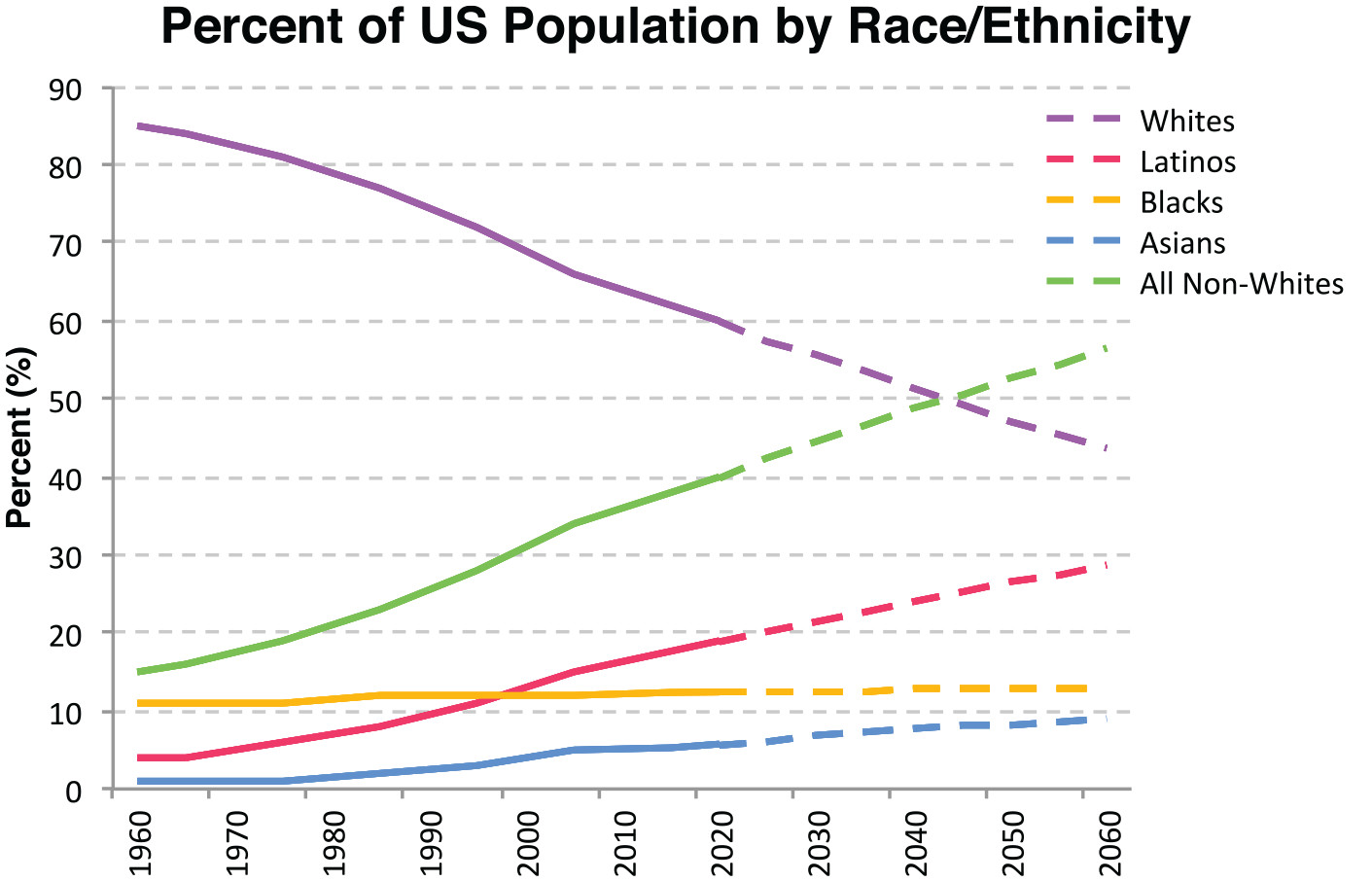

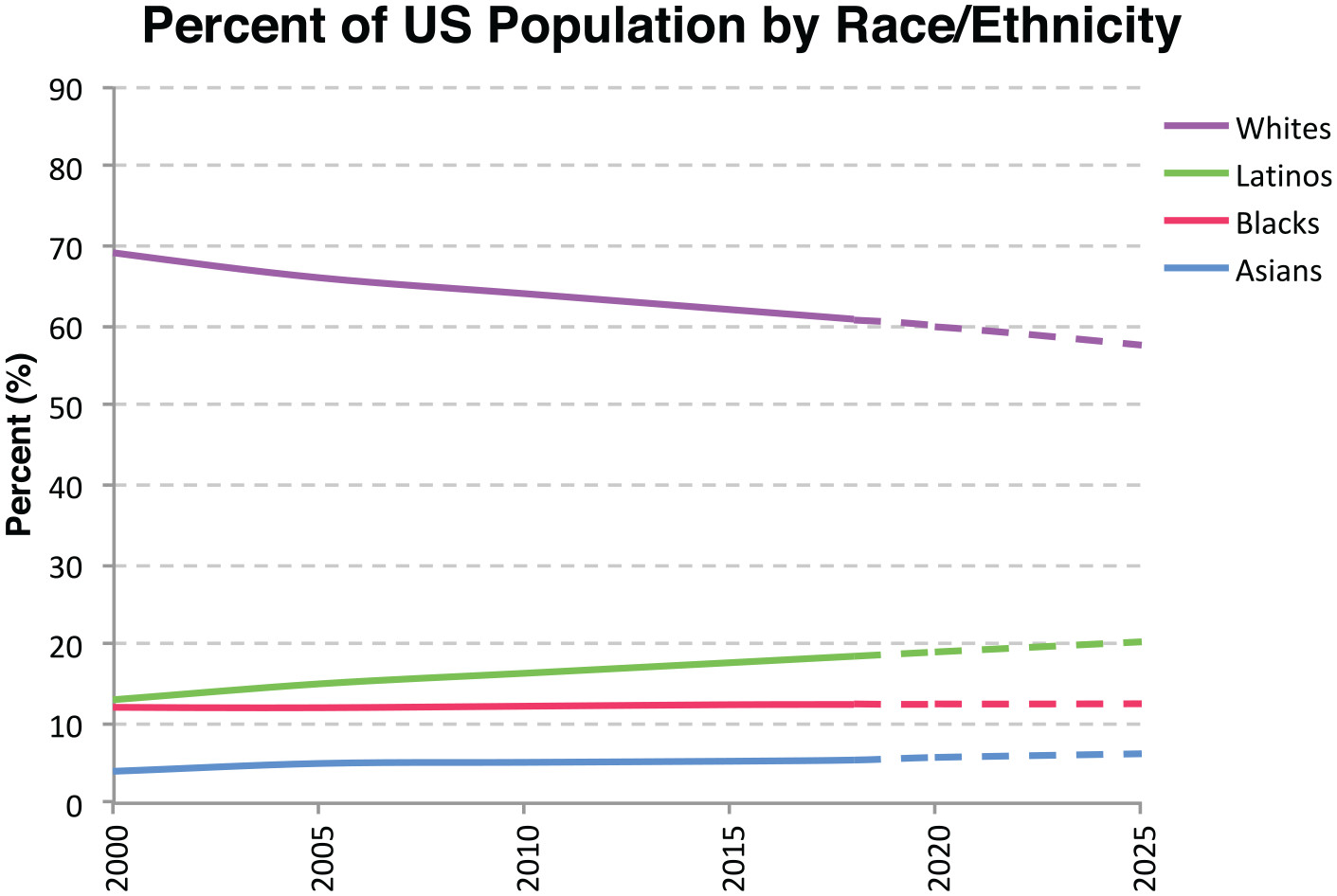

As a result, Latino Americans will play a key role in the evolution

of ethnoracial boundaries in the United States.

Latino Ambiguity

White people who are prompted to think about the changing demographics of the United States are less likely to classify people who are ambiguously White or Latino as “White.” This suggests White people respond to demographic threat by contracting the boundary around Whiteness.

(Abascal 2020:302, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Latino Ambiguity

What does this mean, exactly?

Latino Ambiguity

Studies consistently find that White people are more likely to marry and live near Latinos than Blacks … [T]hese facts are taken to mean that “racial boundaries are more prominent, and the black/white divide more salient than the Asian/white or Latino/white divides” (Lee and Bean 2004:229). However, social scientists have also observed that both intermarriage and integration are lower in areas where immigration is higher … Explanations for this association typically stress structural features of communities rather than individual preferences … (My) findings suggest preferences may also play a role: White people in high-immigration areas might be less likely to count Latinos as candidates for inclusion in White social spaces. In short, where Latinos are more concentrated, the White/Latino boundary is brighter and the benchmark for being considered “honorary Whites” higher.

(Abascal 2020:316, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Latino Ambiguity

More fundamentally, (my) findings imply that White people will increasingly fortify the boundary separating Whites from non-Whites as the Latino and Asian populations continue to grow and the U.S. population diversifies.

(Abascal 2020:316, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Group Exercise I

Abascal’s Estimation Framework

Some Context

Abascal’s Estimation Framework

Some Questions

Group 1

How does Abascal (2020) use Figures A1 and A2 (see the appendix) to adjudicate her guiding assumptions?

Group 2

How does Abascal (2020) use the “faces” in Section E of her Supplemental File to conduct her survey experiment?

Work Session

Work on Your Coding Assignment

For the rest of today’s session,

please work on your first assignment.

Quantifying Nationalism, Conceptualizing Race–

March 6th

Rethinking Nationhood

Nationhood as Institutionalized Form

Nationhood as Practical Category

Nationhood as Contingent Event

Relevant Text

Check out Brubaker (1996).Rethinking Nationhood

Nationhood as Institutionalized Form

Ours is not, as is often asserted, even by as sophisticated a thinker as Anthony Smith, “a world of nations.” It is a world in which nationhood is pervasively institutionalized in the practice of states and the workings of the state system.

(Brubaker 1996:21, EMPHASIS ADDED)

For a relevant paper, see Brubaker (1994).

Rethinking Nationhood

Nationality as a Practical Category

Ours is not, as is often asserted, even by as sophisticated a thinker as Anthony Smith, “a world of nations” … [i]t is a world in which nation is widely, if unevenly, available and resonant as a category of social vision and division.

(Brubaker 1996:21, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Race, ethnicity, and nationality … are not things in the world, but perspectives on the world - not ontological but epistemological realities.

(Brubaker, Loveman, and Stamatov 2004:45, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Rethinking Nationhood

Nationness as a Contingent Event

Ours is not, as is often asserted, even by as sophisticated a thinker as Anthony Smith, “a world of nations” … [i]t is a world in which nationness may suddenly, and powerfully, “happen.”

(Brubaker 1996:21, EMPHASIS ADDED)

As Craig Calhoun has recently argued … identity should be understood as a “changeable product of collective action,” not as its stable underlying cause. Much the same thing could be said about nationness.

(Brubaker 1996:20, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Nationalism in Settled Times

Scholarly Conceptions of Nationalism

| Political (focus on elites’ political projects and discursive practices) |

Quotidian (focus on lived culture, ideas, and sentiments of non-elites) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Ideology (“nationalism” refers to narrow set of ideas) |

Gellner (1983:1): “a political principle, which holds that the political and the national unit should be congruent” | Kosterman & Feshbach (1989:271): “a perception of national superiority and an orientation toward national dominance” |

| Practice (“nationalism” refers to a domain of meaningful social practice) |

Brubaker (2004:116): “a claim on people’s loyalty, on their attention, on their solidarity [. . .] used [. . .] to change the way people see themselves, to mobilize loyalties, kindle energies, and articulate demands” | Brubaker (1996:10): “a heterogeneous set of ‘nation’-oriented idioms, practices, and possibilities that are continuously available or ‘endemic’ in modern cultural and political life” |

Nationalism as Political Project

.jpg)

John Gast’s American Progress

Nationalism as Political Project

Combat et prise de la Crête-à-Pierrot by Auguste Raffet

(engraving by Ernst Hébert)

Quotidian Forms of Nationalism

Quotidian Forms of Nationalism

Popular Nationalism

The Nationalism of Individuals

As Ideology

Nationalist ideology … is not solely the domain of political elites seeking to legitimize their rule over a territorially bounded people. For political psychologists, nationalism is a set of dispositions that cohere at the level of individual actors.

(Bonikowski 2016:429, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Nationalism of Individuals

As Ideology

Political psychologists tend to view nationalism (i.e., chauvinism) as a normative problem … but [p]otentially invidious dispositions toward the nation … are not limited to chauvinism; they also include exclusionary conceptions of national membership, excessive forms of national pride, and strong identification with the nation above all other communities. Furthermore, the standard distinction in this literature between nationalism and its ostensibly benign counterpart, patriotism, is fraught with analytical difficulty.

(Bonikowski 2016:430, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Nationalism of Individuals

As Practice

Nationalism is not only a conscious ideology, it is also a discursive and cognitive frame through which people understand the world, navigate social interactions, engage in coordinated action, and make political claims.

(Bonikowski 2016:430, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Nationalism of Individuals

As Practice

If the operative mode of nationalism-as-ideology is to effect political change in the interest of national sovereignty, nationalism-as-practice involves people thinking, talking, and acting through and with the nation.

(Bonikowski 2016:430, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Nationalism of Individuals

As Practice

Research on nationalism in everyday life … examines how the nation is understood and deployed in routine interactions (Brubaker 1996). This may manifest itself through explicit references to the nation, but just as often,nationalism’s influence is more tacit, expressed in habituated modes of thought, speech, and behavior that take for granted the nation’s cultural and political primacy.

(Bonikowski 2016:431, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Nationalism of Individuals

Bonikowski’s (2016) Primary Goal

To integrate “sociological research on nationalism as a meaningful category of practice and political psychology scholarship on nationalist attitudes.”

(cf. Bonikowski 2016:431)

Schemas of the Nation

A Site of Symbolic Struggle

The nation is not a static cultural object with a single shared meaning, but a site of active political contestation between cultural communities with strikingly different belief systems. Such conflicts are at the heart of contemporary political debates in the United States and Europe.

(Bonikowski 2016:428, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Disparate Understandings of the Nation

[I]f we are to understand how people perceive the nation, we ought to capture the wide range of beliefs and symbolic representations that constitute people’s nation schemas. These are likely to include tropes about the nation’s character, salient national symbols and traditions, perceptions of the nation’s appropriate symbolic boundaries, feelings of pride in the nation’s heritage and its institutions, and views about the nation’s relationship to the rest of the world.

(Bonikowski 2016:437, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Disparate Understandings of the Nation

More simply, popular nationalism taps into the following questions:

Who Is a Legitimate Member of the Nation?

What Are the Nation’s Virtues?

What Is the Nation’s Place in the World?

Crucially, different “thought communities” nested in the general population will have substantively different answers to these questions.

Disparate Understandings of the Nation

Disparate Understandings of the Nation

Disparate Understandings of the Nation

Disparate Understandings of the Nation

Group Exercise II

Measuring Popular Nationalism

In groups of 2-3, discuss how Bonikowski, Feinstein and Bock (2021) capture disparate understandings of nationhood using survey data.

Measuring Popular Nationalism

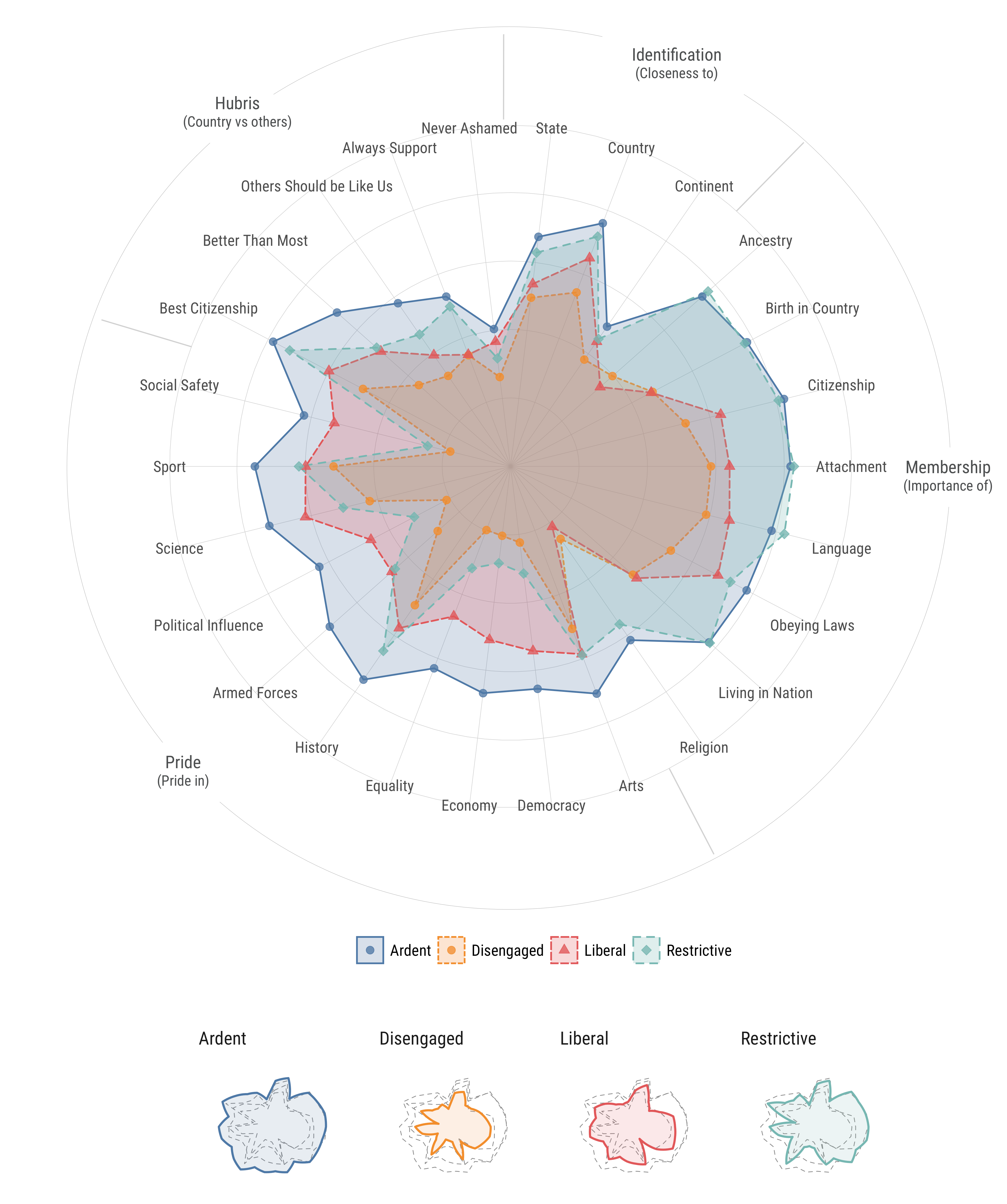

Figure 1 from Soehl and Karim (2021). Click to expand image.

Measuring Popular Nationalism

| Schema | Profile | Identification | Membership Criteria (Exclusionism) | Pride | Hubris |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ardent | High | High | High | High | |

| Disengaged | Low | Low | Low | Low | |

| Liberal | Moderate | Low to Moderate | High | Moderate | |

| Restrictive | Moderate | High | Low to Moderate | Moderate to High |

Race, Class, Politics

The Enduring Significance of Race

The Politics of Police

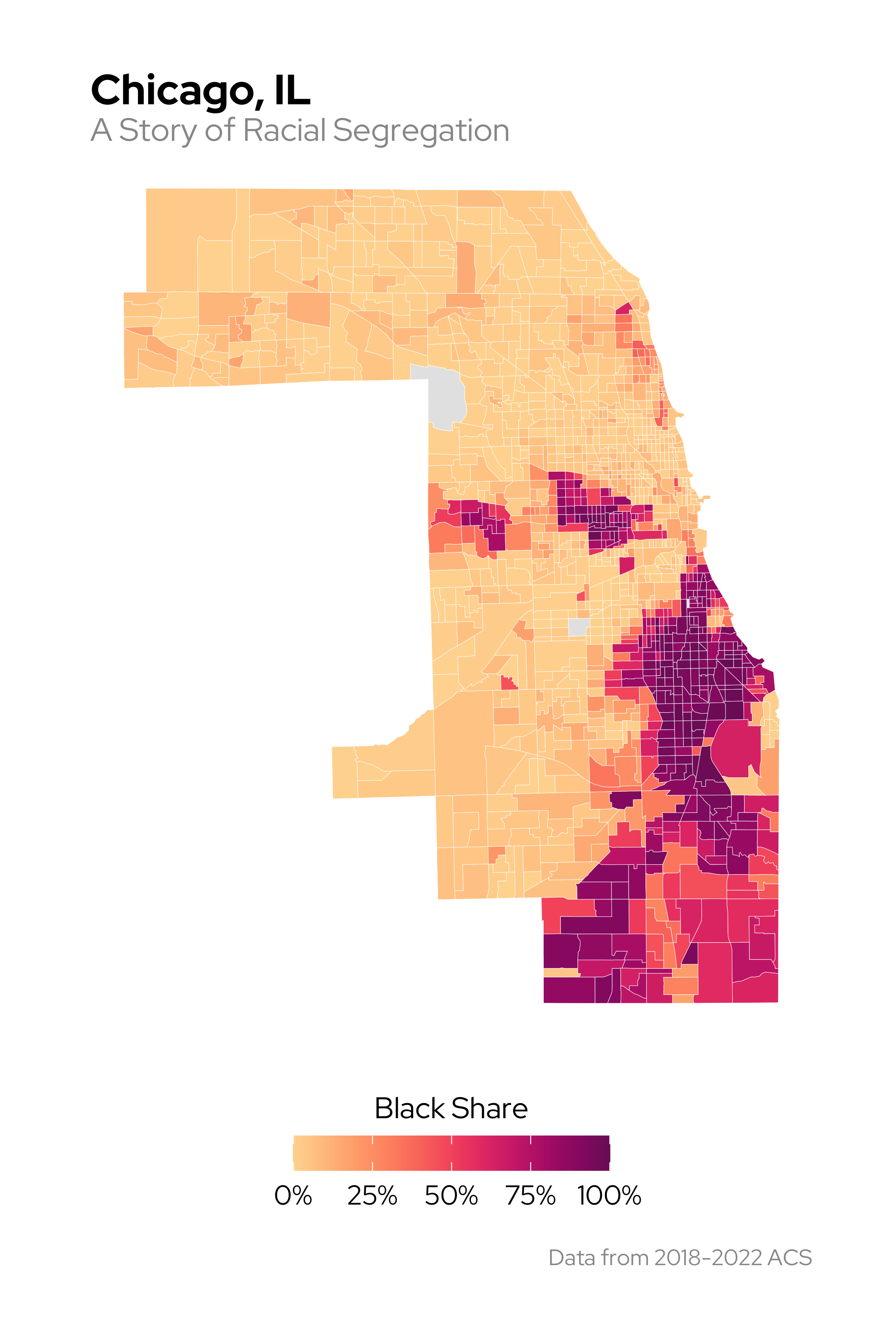

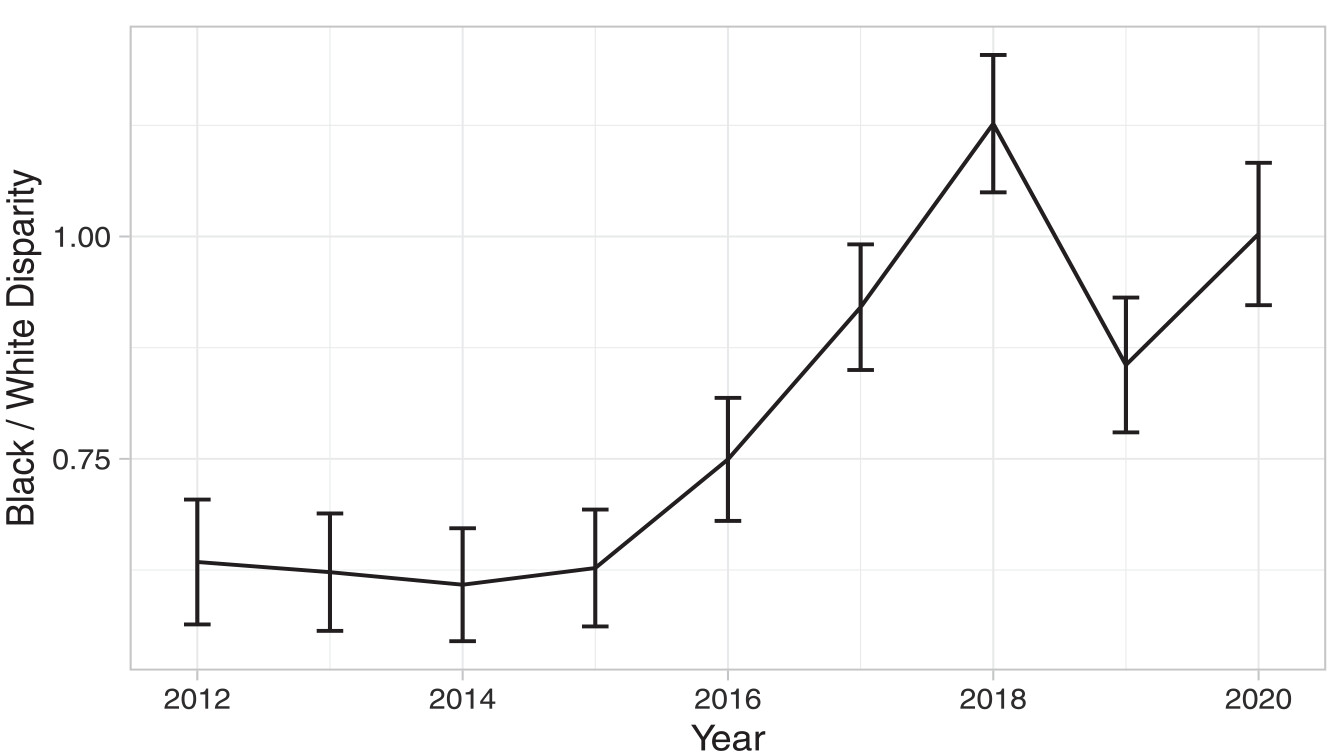

Through an analysis of millions of highway patrol stops between 2012 and 2020, I study the treatment of Black and Hispanic motorists compared to White motorists by officers who vary in their party affiliation. I find that White officers registered with the Republican Party are significantly more likely to search Black motorists compared to White motorists than White officers registered with the Democratic Party. Although this party effect remained relatively stable from 2013 to 2020, I show that after 2016, racial disparities among all White officers increased, corresponding with the election of Donald Trump and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement. These results are robust to an array of alternative empirical tests.

(Donahue 2023:657, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Politics of Police

Figure 1 from Donahue (2023).

The Use of Lethal Force

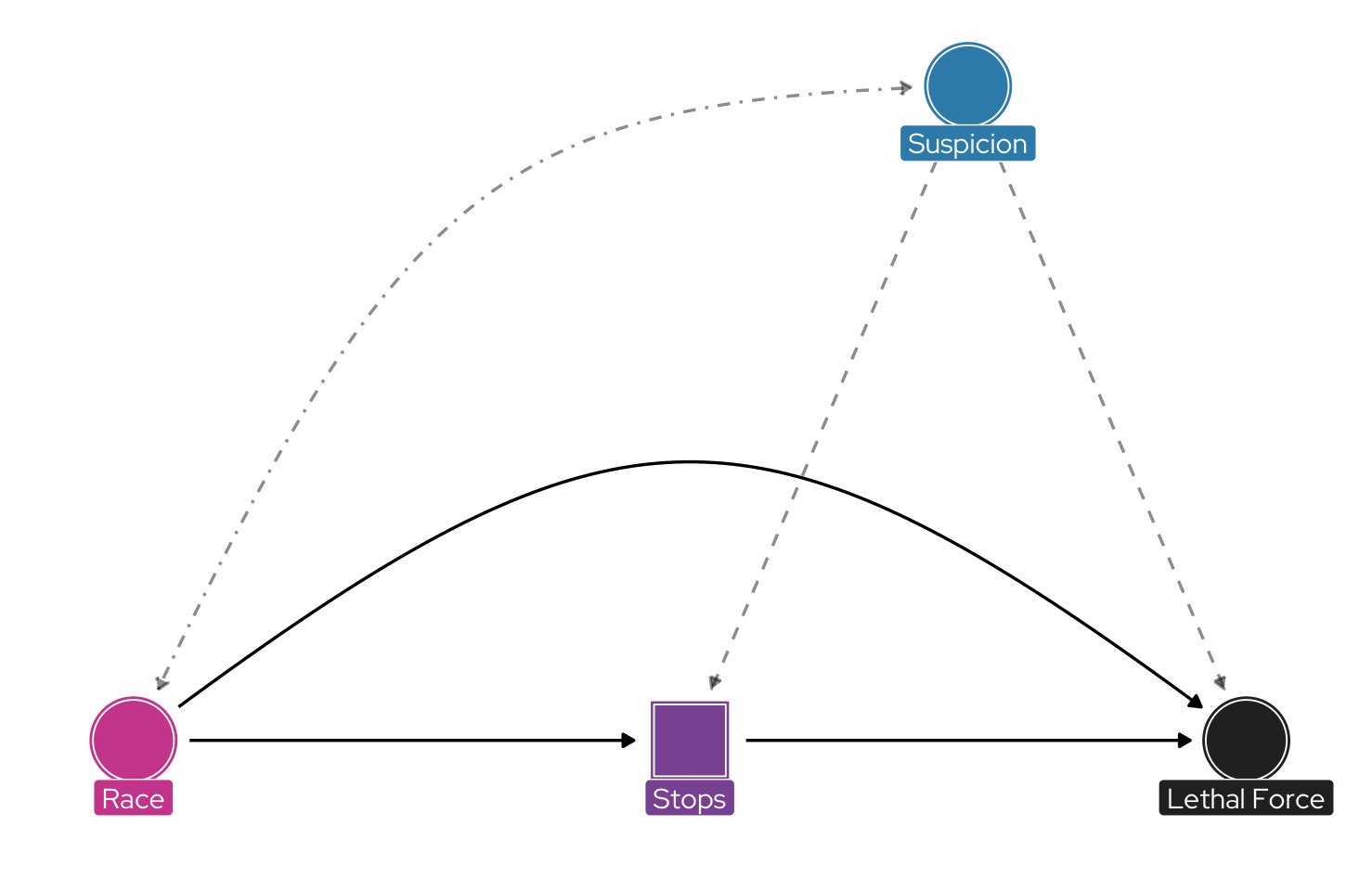

Do Not Condition on a Collider

Adaptation of Figure 1 from Knox, Lowe and Mummolo (2020).

Group Exercise III

Race As a Resource Signal?

Torres (2024) argues that race can be understood as a resource signal. In groups of 2-3, discuss what this means in concrete terms—and how Torres adduced quantitative evidence to support his propositions.

Work Session

Work on Your Coding Assignment

For the rest of today’s session,

please work on your first assignment.

Enjoy the Weekend

References

Note: Scroll to access the entire bibliography